Page 2 - Page 3

Page 4 - Page 5

Page 6 - Page 7

Page 8 - Page 9

Page 10 - Page 11

Page 12 - Page 13

Page 14 - Page 15

Page 16 - Page 17

Page 18 -Page 19

Page 20 - Page 21

Page 22 - Page 23

Page 24 - Page 25

Page 26 - Page 27

Page 28 - Page 29

Page 30 - Page 31

Page 32 - Page 33

Page 34 - Page 35

Page 36 - Page 37

Page 38 - Page 39

Page 40- Page 41

Page 42 - Page 43

Page 44 - Page 45

Page 46 - Page 47

Of the many thousands of manuscripts produced in Mesoamerica before the Spanish conquest there remain today little more than a dozen, some in a fragmentary state, scattered across the libraries of Europe and America. Of post-conquest date there survive several hundred, of which many show relatively little Spanish influence as regards style, although written on cloth or European paper as opposed to the indigenous amatl, maguey fibre or deerskin.

The native tradition continued for some time after the conquest as, after the wholesale destruction of the books by the misguided zeal of the Spanish priests and conquistadors, documents still had to be produced to assist the Spaniards in the administration of the conquered province. Examples of these documents are the Codex Mendoza and the Matricula de Tributos, which record the amount of tribute paid to the city of Tenochtitlán with details of the towns it came from. The Spaniards also used genealogical tables, compiled in the traditional form, to settle lawsuits and select indigenous chiefs to act as vassal rulers. Friar Nicholas Tester even attempted to adapt the Aztec pictograms to form a syllabic script. Thus the sign for pantli, a flag, became the syllable pa in Paternoster. This idea did not receive a wide currency for many Aztecs who had come under the influence of the friars learned the Latin alphabet and adapted it to the Nahuatl tongue. Ixtlilxochitl and Tezozomoc, two indigenous princes, drew on lost sources, probably in the form of pre-Columbian screenfold manuscripts, for their histories of their own communities. In other areas of Mesoamerica too the native methods were abandoned in favour of the Latin alphabet. The Maya Popol Vuh is a collection of traditions that would formerly have been recorded in hieroglyphic screenfold manuscripts.

It is the tribute lists that tell us how widespread the practice of recording information in manuscripts was before the Spanish conquest. They show that 480,000 sheets of paper were exacted in tribute by Tenochtitlán every year. Such a large consumption would be quite possible in the administration of the city, which was at the head of a large empire and itself had more than 100,000 inhabitants.

The majority of the surviving pre-Columbian manuscripts come from the Mixtec area, and it is probably from them that the Aztecs inherited the practice of compiling manuscripts. A scene in the Mapa Quinatzin, a Texcocan document from the valley of Mexico, shows the arrival in about 1300 of "the people that return" who supposedly introduced or reintroduced writing into that area. The valley manuscripts also indicate a more cursive style which would suggest a people adapting to their own use a foreign invention without being inhibited by traditional forms of presentation. A third piece of evidence is the fact that the Mixtec codices as interpreted by Alfonso Caso record events dating back to the year 692, which is some two hundred years before the historic horizon in the valley of Mexico and would indicate a correspondingly earlier use of writing for recording historical events.

The earliest surviving screenfold manuscript, the Codex Dresden, which was probably compiled around the 13th century, is from the lowland Maya area of Yucatan and it is from the Maya or the neighbouring Zapotecs that the Mixtecs learned to write, an hypothesis suggested by the presence of the bar-and-dot method of numeration in early Mixtec manuscripts and its absence in later ones.

The Maya seem to have learned the craft of writing from the Olmec culture in the late formative era, around the first centuries of the common era, which means that on the arrival of the Spaniards there was a two millennium tradition of literacy in Mesoamerica.

The primary effect of the illustrations in the manuscripts was not intended to be artistic. The painter had the task not merely of creating an aesthetically pleasing composition but of recording ideas, including abstract concepts such a relationship and divinity. Thus artistic considerations had frequently to be sacrificed for the sake of clarity of meaning. Persons who bore a specific relationship to each other had to be juxtaposed in an appropriate manner in the manuscripts even if this meant overcrowding. Also the need for conventional methods of representation for ease of understanding meant that experiment and the cultivation of an individual style was discouraged.

With the development of more advanced forms of writing, as with the Maya, the illustrations were relieved of this burden and greater freedom of expression was the result. In Codex Dresden the illustrations are practically redundant as the glyph of the god depicted frequently occurs in the accompanying text and the illustration serves not to carry the message but to reinforce and elaborate it. The result is a more flowing style and one which contrasts with the formal stiffness of the Mixtecs and Aztecs.

Friar Diego Landa records that the Maya were greatly upset when he burned their manuscripts at Mani in 1562. This is quite understandable for they embodied their whole culture in a permanent form. Writing is the true sign of civilization, as it denotes a society complex enough to warrant the compilation of permanent records to facilitate its continued existence. It also reflects the emergence of individuality in human terms, as opposed to the consideration of a person merely by the position within the religious or social structure, through the documentation of actual events in a form more permanent and definite than folk memory. Is it any wonder that the attitude of the painter to his craft, as reflected in Aztec poetry, is one of immense pride.

[The foregoing has been transcribed from the original manuscript with a few minor changes to correct infelicities of style. In the early 1960s the deciphering of Maya hieroglyphs was at a relatively early stage as its essentially syllabic nature had only recently been recognized. In the half century since then great progress has been made and the high status of the scribe in Maya society has been confirmed. It is satisfying that the conclusions reached in this piece of juvenilia have been borne out.]

Ian Maxted

June 2020

By codex

Borbonicus 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 20, 33, 36, 39, 41, 43, 45It is the tribute lists that tell us how widespread the practice of recording information in manuscripts was before the Spanish conquest. They show that 480,000 sheets of paper were exacted in tribute by Tenochtitlán every year. Such a large consumption would be quite possible in the administration of the city, which was at the head of a large empire and itself had more than 100,000 inhabitants.

The majority of the surviving pre-Columbian manuscripts come from the Mixtec area, and it is probably from them that the Aztecs inherited the practice of compiling manuscripts. A scene in the Mapa Quinatzin, a Texcocan document from the valley of Mexico, shows the arrival in about 1300 of "the people that return" who supposedly introduced or reintroduced writing into that area. The valley manuscripts also indicate a more cursive style which would suggest a people adapting to their own use a foreign invention without being inhibited by traditional forms of presentation. A third piece of evidence is the fact that the Mixtec codices as interpreted by Alfonso Caso record events dating back to the year 692, which is some two hundred years before the historic horizon in the valley of Mexico and would indicate a correspondingly earlier use of writing for recording historical events.

The earliest surviving screenfold manuscript, the Codex Dresden, which was probably compiled around the 13th century, is from the lowland Maya area of Yucatan and it is from the Maya or the neighbouring Zapotecs that the Mixtecs learned to write, an hypothesis suggested by the presence of the bar-and-dot method of numeration in early Mixtec manuscripts and its absence in later ones.

The Maya seem to have learned the craft of writing from the Olmec culture in the late formative era, around the first centuries of the common era, which means that on the arrival of the Spaniards there was a two millennium tradition of literacy in Mesoamerica.

The primary effect of the illustrations in the manuscripts was not intended to be artistic. The painter had the task not merely of creating an aesthetically pleasing composition but of recording ideas, including abstract concepts such a relationship and divinity. Thus artistic considerations had frequently to be sacrificed for the sake of clarity of meaning. Persons who bore a specific relationship to each other had to be juxtaposed in an appropriate manner in the manuscripts even if this meant overcrowding. Also the need for conventional methods of representation for ease of understanding meant that experiment and the cultivation of an individual style was discouraged.

With the development of more advanced forms of writing, as with the Maya, the illustrations were relieved of this burden and greater freedom of expression was the result. In Codex Dresden the illustrations are practically redundant as the glyph of the god depicted frequently occurs in the accompanying text and the illustration serves not to carry the message but to reinforce and elaborate it. The result is a more flowing style and one which contrasts with the formal stiffness of the Mixtecs and Aztecs.

Friar Diego Landa records that the Maya were greatly upset when he burned their manuscripts at Mani in 1562. This is quite understandable for they embodied their whole culture in a permanent form. Writing is the true sign of civilization, as it denotes a society complex enough to warrant the compilation of permanent records to facilitate its continued existence. It also reflects the emergence of individuality in human terms, as opposed to the consideration of a person merely by the position within the religious or social structure, through the documentation of actual events in a form more permanent and definite than folk memory. Is it any wonder that the attitude of the painter to his craft, as reflected in Aztec poetry, is one of immense pride.

[The foregoing has been transcribed from the original manuscript with a few minor changes to correct infelicities of style. In the early 1960s the deciphering of Maya hieroglyphs was at a relatively early stage as its essentially syllabic nature had only recently been recognized. In the half century since then great progress has been made and the high status of the scribe in Maya society has been confirmed. It is satisfying that the conclusions reached in this piece of juvenilia have been borne out.]

Ian Maxted

June 2020

Index to illustrations

By codex

Borgia 2, 5, 6, 7, 19, 25, 28, 29, 37, 38, 43, 44

Fejérváry-Mayer 9, 11, 35, 37

Florentino 43

Laud 13, 17, 21, 27, 32, 34

Magliabecchiano 4, 8, 14, 15, 30, 47

Matritense IV 45

Telleriano Remensis 26

Vaticanus A 22, 23

By deity

Centeotl or Cinteotl - god of maize 19

Chalchiutlicue - she of the jade skirt, goddess of lakes and streams 18

Cihuapipiltin - noblewomen, goddesses of the crossroads 43

Ehecatl - wind, manifestation of Queztalcoatl as god of wind 4, 7

Heavens and hells 22

Huitzilopochtli - hummingbird of the south, the supreme deity of the Aztecs 41

Huixtocihuatl - fertility goddess, presiding over salt 45

Itztli - obsidian knife, god of scrifice, linked to Tezcatlipoca 45

Itztlacoliuhqui - curved obsidian blade, god of frost 43

Macuilxochitl - five flower, manifestation of Xochipilli, patron of courtiers and games 14

Mayahuel - goddess of the maguey plant 20, 21

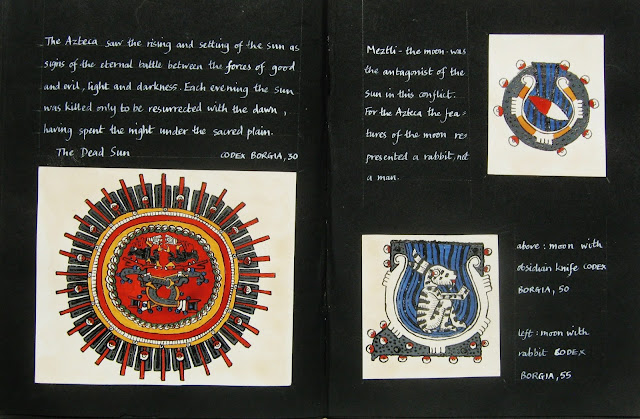

Metztli - moon, god of the moon in the guise of a rabbit 29

Mictlancihuatl - lady of the underworld, goddess of death 34, 35

Mictlantecuhtli - lord of the underworld, god of death 32, 33, 47

Mixcoatl - cloud serpent, hunting god 43

Omecihuatl or Tonacihuatl - lady of duality 26

Ometecuhtli or Tonatecuhtli - lord of duality, ruler of the highest heaven 25, 27

Quetzalcoatl - feathered serpent, god of rain, wind, priests and merchants 4, 36

Teoyaomiqui or Huahuantli 44

Tepeyollotl - heart of the mountains, god of earthquakes 43

Tezcatlipoca - smoking mirror, god of rulers, sorcerers and warriors 5, 6

Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli - lord of the dawn house, Quetzalcoatl as god of Venus the morning star 37

Tlaloc - god of rain and lightning 16, 17

Tlazoteotl filth god, goddess of purification 10, 11

Tonatiuh - sun god 2, 28

Tztimitl - star demons of darkness 30

Xilonen - goddess of maize 8

Xipe Totec - the flayed one, patron of goldsmiths and warriors 9

Xochipilli - flower prince, patron of flowers, dancing, feasting, painting 14

Tonallo - symbol for the soul, spirit, day, heat, destiny 15

Xochiquetzal - flower quetzal, patron of artists and childbirth 12, 13

Xolotl - dog, companion of Quetzalcoatl, associated with sickness, deformity and twins 38, 39

A list of Mesoamerican manuscripts

Although exhaustive in the light of our present state of knowledge [in 1962] as far as the pre-Columbian manuscripts are concerned, this list only mentions a very few of the more well-known post-conquest manuscripts, of which there are several hundred, mostly on European paper.

[The following manuscripts were listed with notes on contents, present location and publications containing facsimiles of the original. A fuller updated listing is in preparation.]

- Codex Becker I or Manuscript of Cacique (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Codex Becker II (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Bodley. (Mixtec, colonial, 1521?)

- Codex Borbonicus. (Aztec, colonial, 1530?)

- Codex Borgia. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Colombino or Doremberg. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Cospi or Bologna. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Culto de Sol. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Dresdensis. (Maya, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Codex Fejérváry -Mayer. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Codex Laud. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Codex Peresiano. (Maya, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Selden. (Mixtec, colonial, 1550?)

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis (Aztec, colonial, 1530?)

- Codex Tro-Cortesiano. (Maya, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Vaticanus B (no. 3773) (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Vienna (recto) (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Codex Vienna (verso) (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Codex Zouche-Nuttall. (Mixtec, pre-Columbian, early style)

- Plano en Papel de Maguey. (Aztec, pre-Columbian, late style)

- Tonalamatl of Aubin. (Aztec, possibly pre-Columbian, late style)

This page last updated 6 June 2020