Ten astounding literary inventions

Heritage open days in Exeter, 9-18 September 2022.

Libraries, museums and archives in Exeter overflow with the products of astounding inventions which have helped to record human achievements and discoveries across the millennia and conserve our written and graphic heritage.

| Astounding inventions: |

1. The alphabet.

2. The codex book.

3. Paper.

4. The woodcut.

5. Printing.

6. Engraving.

7. Lithography.

8. Photography.

9. The moving image.

10. Digitisation.

👉 Hunt for them in Exeter's heritage collections:

1. The alphabet.

The twenty-six letters which make up the alphabet in which the English language is written had their origin among Semitic workers in Egypt who some time around the 19th century BCE adapted a selection of Egyptian hieroglyphs to represent the initial sound of the word represented by the sign. The resulting series of signs was adapted by the Phoenicians in the 11th century BCE and from them passed to the Greeks around 800 BCE and the Romans in the 7th century BCE. The table below is a simplified account of the history of each letter. Some letters, such as G, J, U,V, W and Y are later additions, others were not adopted by the Romans.

For the first time scripts were now completely phonetic, being a written representation of spoken words. It also dramatically reduced the number of characters in a script from hundreds or even thousands to between twenty and forty, making literacy more widely accessible and paving the way for printing, or more specifically printing with movable type.

Roman tile bearing incised alphabet, ca. 60 CE. Royal Albert Memorial Museum.

This tile was made in Exeter for the hypocaust of the legionary bath-house in Cathedral Close. The tile has been incised before firing with the first letters of the Roman alphabet, finishing with the letter "F". It provides the earliest direct evidence of literacy in Devon. The Royal Albert Memorial Museum also holds examples of writing in Greek and other early alphabetic scripts. During Heritage Open Days 2022 it has an Astounding Adventures Trail and other activities.

2. The codex book.

The medium for storing and transmitting literary texts in the Classical world was the scroll but about 85 CE early examples of literary codices are mentioned by the Latin poet Martial. The word caudex means tree trunk or block of wood and a transitional stage was the stringing together of wooden writing tablets to form a pugillaris (literally fist book). Wood tablets were replaced by folded vellum sheets stitched together, at first in small notebooks but it was soon discovered that hundreds of such folios (leaves) could be bound between boards. A scroll could hold just one book of the the Iliad, or the Bible - the librarian of Alexandria Callimachus said "a big book is a big evil" - but a codex could hold Homer's entire epic poem or the whole Old or New Testament. The earliest codex that is substantially complete is the biblical Codex Sinaiticus from the fourth century. The earliest illustrated literary text is the Vergilius Vaticanus (Vatican Vergil), dating from around 400 CE.

The development of the codex book gave rise to a new craft, that of the bookbinder. The earliest book in Exeter Library Special Collections has lost much of its binding, but was conserved in that state because it shows the structure of a medieval bookbinding. The folded sheets are gathered together in sections and, using a sewing frame, are stitched onto hemp cords, in this case double cords. The thread passes out from the centre fold between the two cords, then underneath them and back between them, thus fixing each gathering with four firm knots. The cords pass through the wooden boards, along a recessed groove and are pegged through the board again. The whole was covered with leather and blind tooled with a pattern which has left indentations on the wooden board where the leather is missing. Volumes would often have metal bosses, clasps, locks or chains, as manuscript books were very precious and their contents often sacred.

Nicolaus Panormitanus de Tudeschis, Lectura super v. libri decretalium.

[Basel] : [Johann Besiken], 1480. Copy in Exeter Library Special Collections

Early examples of manuscript codex books are to be found in Exeter Cathedral Library. During Heritage Open Days 2022 it is offering tours of the Library. the Exeter Book of Old English verse dating from around 960-980 and the Exon Domesday, dating from 1086. Facsimiles of early codices can also be found in libraries in Exeter and there are also many examples online. One of the riddles in the Exeter Book gives a description of the preparation of a manuscript codex, probably a gospel book.

The book riddle from the Exeter Book of Old English poetry. Exeter Cathedral Library

A translation of the book riddle into modern alliterative verse is available in the Exeter Working Papers in Book History.

3. Paper.

In 105 CE Cai Lun (or Ts'ai Lun), a eunuch and official of the Chinese Imperial Court, reported to the Emperor of China that paper had been invented. Previously silk or bamboo was used but the new invention used pulped bark of trees, hemp, old rags, and fishing nets drained through wooden sieves. It spread slowly across Asia, reaching Europe in Moorish Spain at Xativa by 1151 and Christian Europe at Fabriano by 1282. The origins of the English use of paper go back to as early as 1275, when Edward I instructed the mayor and corporation of London to change their bureaucratic processes, using paper books. There was no paper made in England until John Tate established his mill in Hertford some time before 1494. Papermaking did not reach Exeter until the 17th century and there have been no active paper mills in Exeter since the 1980s. A walk along the River Exe will pass the sites of all Exeter's former paper mills:

Countess Wear paper mills, Upper Wear (1704-1884) and nearby Lower Wear (1778-1829)

Trew's Weir Paper Mill (1834-1982) now apartments

The Mill on the Exe, on the site of Head Weir paper mill, (1798-1967)

The site of Exwick Paper Mill (1806-1860), now a housing estate

Early Devon documents on paper include a deed dated 1371 in the records of the Carew Family of Haccombe House (Devon Archives: 2723M), and the letters of John Shillingford, mayor of Exeter, written between 1447 and 1450, were all on paper (Exeter City Records, miscellaneous rolls boxes 100 and 101).

The broadsheet below in the Westcountry Studies Library is on a whole sheet of handmade paper and held to the light the watermark and countermark can be seen.

A list of the freemen and freeholders who voted at the election for a representative in Parliament for the city of Exeter, in the room of John Walter, Esquire, John Baring and John Burridge Cholwich, Esquires, candidates. Exeter: Trewman, 1776. (Westcountry Studies Library: LE 1776).

The paper may have been imported from the Netherlands. The watermark is similar to that used by Piet van der Ley who operated the De Bonsem and De Wever mills in Koog aan de Zaan in Holland from 1674. The countermark is used by Jean Villedary, a name borne by several generations of a family who operated mills at Vraichamp, Beauvais and La Couronne near Angoulême from 1668 to 1758 The VL mark was appropriated by many makers including some in England, as a mark of quality, and this may be what Villedary did. The Villedary family had many links with Holland and in 1758 moved to Hattem in Guelderland, where they continued to make paper.

4. The woodcut.

Because of the nature of the scripts of eastern Asia, woodcuts have been used to print texts on paper since at least the eighth century, and they have been used to decorate textiles and produce images, often of holy figures, but also banknotes. The design was cut on a flat, smooth surface of a block of wood, the areas intended to receive ink being left proud and the white background cut away. Prints were taken by rubbing the back of the paper onto the inked surface, which meant that normally only one side of the paper could be used. Woodcuts appear in Europe at the close of the 14th century and are often images of saints but there are also playing cards. It is tedious to cut lengthy texts in wood and the few woodcut blockbooks mainly date from the period after the invention of printing.

In Exeter tillet blocks are examples of woodblocks with the image engraved in relief. They were used in Exeter, particularly during the 18th century to stamp a trade mark onto the wrappers (or tillets) of bundles of cloth. This was probably done at the Custom House on the Quay where examples are on display. There are events at Quay Words during Heritage Open Days 2022. The Royal Albert Memorial Museum also has examples of tittle blocks and Tuckers Hall, also open during Heritage Open Days 2022, has a fascinating exhibition tracing Exeter's woollen industries through archives and other historical documents.

The Ship of fools illustrated in the next section uses woodcut illustrations. They have the advantage over engravings of being capable of being printed together with the text on the same printing press. Engraved and lithographic illustrations require different types of press. Because they can printed at the same time as text woodcuts, and from the late 18th century the more detailed wood engravings, are used not only for illustrations but also for decoration, initial letters and title page borders.

5. Printing.

While there had been earlier printing in the Far East, this had been mainly from woodblocks and it is generally accepted that printing with movable type was developed by Johann Gutenberg between about 1438 and 1452 at first in Strasbourg and later in Mainz. It was a coming together of various technical processes: the ability to cut punches for individual letters, the invention of a hand-held mould to enable the rapid casting of large quantities of each letter, the development of a suitable lead alloy, and of a thick ink that would adhere to metal. The final element was the construction of a wooden hand press which could take an impression from the raised surface of the type, which had been composed letter by letter and locked within a forme or frame and laid on the bed of the press.

Printing spread across Europe from Mainz, reaching Italy in 1465, Switzerland in 1468, France and probably the Netherlands in 1470, Spain in 1471, Hungary in 1473, Poland in 1473 and England in 1476. This rapid spread of printing, with books appearing in editions of several hundred copies, was only possible because of the availability of paper. By 1494 when the poet Sebastian Brant published Das Narrenschiff (the ship of fools) he could describe how printing had brought the acquisition of book within the grasp of much greater numbers of people, even including fools. In fact the book fool is the first to be described in a long series of fools, each of them with a lively woodcut illustration.

The work was widely translated and the translator Alexander Barclay was the first Devonian to get into print - he was in Ottery St Mary when the first edition was published in 1509.

Barclay, Alexander. Stultifera navis = The ship of fools (2nd edition, 1570)

Westcountry Studies Library sx821/BAR.

An interesting early pamphlet held by the Westcountry Studies Library illustrates two inventions: paper and printing. It is an early example of Exeter printing, showing its use in reporting current events, and also, being unfolded, shows how printers had to impose pages so that, once folded and stitched they were in the right order. In this example the inner and outer formes would have been imposed on the bed of the press side by side so that, once one side of the sheets of paper had been printed the heap would be turned end to end and the other side printed. Each sheet would then have two copies of the eight page pamphlet correctly backed up. This technique was known as "work and turn".

Five of the letters which passed between C. Gyllenborg ... (Exeter: Joseph Bliss, 1717)

Westcountry Studies Library: LE 1717.

The images above show the outer forme of the half sheet and an enlarged drawing of the watermark which is normally located centrally on one half of the sheet. The other half of the sheet would probably have had a smaller countermark.

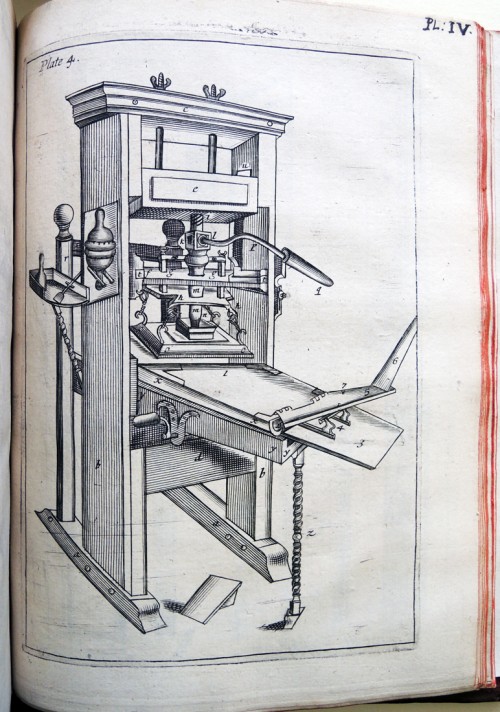

In the Exeter Library Special Collectons is a key work in the history of printing, a well-illustrated and detailed account of the wooden hand press which produced all letterpress publications in Europe from 1455 until the early 19th century, when mechanisation began. Joseph Moxon (1627-1691), printer and "hydrographer to the Kings most Excellent Majesty" published "at the sign of Atlas on Ludgate-Hill" the first English printer's manual as part of Mechanick exercises. Or, the doctrine of handy-works. Illustrated by plates, it was an early example of a publication in monthly numbered parts. Number 1 appeared on "Jan. 1. 1677" [actually 1678] and it appeared regularly until no. 6 (June 1-July 1, 1678). After that the parts appeared less and less frequently, numbers 7-9 being dated 1679 and numbers 10-14 1680. Despite the apparent lack of success, Moxon appears to have held onto unsold sheets and reissued them in 1683-84 as a single volume and there were various later editions and reissues until 1703.

Engraved plate showing the hand printing press from Princeton University's copy of Moxon

Exeter Library holds an example of an early facsimile reprint: Moxon's mechanick exercises, or, The doctrine of handy works applied to the art of printing : a literal reprint in two volumes of the first edition published in the year 1683, with preface and notes by Theo L. De Vinne (New-York : The Typothetæ of the City of New-York, 1896). The two volumes are in a limited edition of 450 copies, "All copies on hand-made Holland paper and printed from types ...". There is also a later edition: Mechanick exercises on the whole art of printing (1683-4), by Joseph Moxon ; edited by Herbert Davis & Harry Carter (Oxford University Press, 1958 ; 2nd edition 1962 ; reprint by Dover, 1978). Copies of this are available in Exeter Libraries.

Another publication of Joseph Moxon shows the key role of printing in spreading knowledge. Only three copies of this work were known in British libraries (Bodleian Library, Wellcome Library and Manchester University Library), so it is much rarer than Gutenberg's 42-line Bible. To these can be added a fourth copy, discovered in an attic in Exmouth and transferred to Exeter Library Special Collections. It is:

An exact survey of the microcosmus or little world : being an anatomie, of the bodies of man and woman wherein the skin, veins, nerves, muscles, bones, sinews and ligaments are accurately delineated. And curiously pasted together, so as at first sight you may behold all the outward parts of man and woman. And by turning up the several dissections of the paper take a view of all their inwards. With alphabetical referrences [sic] to every member and part of the body. Usefull for all doctors, chirurgeons, &c. As also for painters, carvers, and all persons that desire to be acquainted with the parts, and their names, in the bodies of man, or woman; Set forth by Michael Spaher of Tyrol ; And English'd by John Ireton ; And lastly perused and corrected, by several rare anatomists.

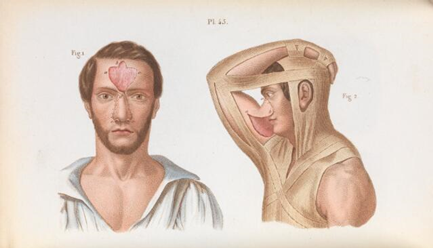

The lengthy title says what is in the box. It is the work of Johann Remmelin (1583-1632) and has the imprint: London: Printed by Joseph Moxon, and sold at his shop 1670. It is a large format folio item with eight unnumbered pages, four pages of letterpress and four leaves of engraved plates which have superimposed moveable flaps. This edition uses the plates of the Dutch edition of 1667, whereas later English editions have re-engraved plates. The Dutch plates in turn were based on the 1613 Latin edition, instead of the revised 1619 edition which formed the basis of Latin and German editions. Thus it can be seen in the wider European context of an important medical text distributed in several languages with the international exchange of the meticulously engraved plates.

Medecine is a good example of the way in which printing, often with woodcut and engraved illustrations, helped to spread knowledge and ideas. Libraries in Exeter hold rich collections of early medical literature. Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives hold several early collections of medical book, notably the library of Exeter physician Thomas Glass, bequeathed in 1786. In 2016 Exeter Library Special Collections hosted an exhibition "Sickness in the Archive" assisted by the Wellcome Trust and the University of Exeter.

A coloured plate from the exhibition Art and Surgery

With the Devon and Exeter Medical Heritage Trust St Nicholas Priory is hosting an interactive exhibition entitled "Art and Surgery" during Heritage Open Days 2022. Exeter is home to many medical and surgical inventions and innovations. Prehaps the best known is the Exeter Hip, created by orthopaedic surgeon Professor Robin Ling and University of Exeter engineer Dr Clive Lee, which was first implanted in 1970.

6. Engraving.

Intaglio printing, where the ink which produces the image is taken from the recessed areas of the copperplate was developed about the same time as letterpress . The plate is warmed, inked and then wiped clean, leaving ink in the recessed areas. It is then passed through the press with damped paper placed on the plate. A board below and felts above help to spread the considerable pressure. The press, known as a rolling press, operates on the principle of a mangle, concentrating the pressure in a single strip. This different type of press means that the illustrations cannot be printed at the same time as letterpress text, although much finer detail is possible than with woodcut illustrations. The considerable pressure also results in a plate-line which is often visible outside the area of the print, unless it has been cut off or the print has been produced by an off-set process.

A rolling press in action, an engraving from the French Encyclopédie (1751-1772)

Copper line engraving is the earliest intaglio process, the first dated print appearing in 1446.

This work by the Exeter physician and antiquary William Musgrave (1655–1721) is an example of scholarly printing in Latin, unusual for Exeter. It is also an example of the use of engraving, as Musgrave's copperplate illustrations are engraved by Joseph Coles, the first Exeter engraver.

William Musgrave, Iulii Vitalis epitaphium cum notis criticis explicatione; ... Quibus accedit Illius, ad Cl. Goetzium, de Puteolana & Baiana inscriptionibus epistola. Iscae Dumnoniorum : Typis Farleyanis : sumtibis Philippi Yeo, bibliopolae. Veneunt etiam Londinii, & in utraque Academia. MDCCXI. [1711].

(Westcountry Studies Library: sWES/0043/MUS).

While line engraving was the earliest technique employed, as in the illustrations to Musgrave's book , there are a number of process which attempt to reproduce tones as opposed to line effects.

- Stipple. The plate is pierced with roulettes and multi-pointed tools to produce a close mass of dots. It was used from the mid 18th century

- Mezzotint. This is a tone process invented in the 1640s by Ludwig von Siegen. Here the whole plate is roughened with a rocker which throws up burr in all directions. The burr is scraped down in areas that are intended not to print black

- Etching. Here the lines are incised into the plate by the effect of acid, not by the pressure of the burin. The metal plate is protected by a transparent waxy ground which is rolled or dabbed on and the back and sides protected by varnish. The face is smoked to blacken it and the design is drawn on with a needle to break through the ground. The plate is then placed in an acid bath.

- Aquatint. This produces a much lighter tone effect than mezzotint, and is therefore better for giving the effect of a wash or watercolour. The plate is coated with a porous granular etching ground by covering it with resin. The acid bites round the grains leaving a fine network of lines around white dots. A graduation of tone can be achieved by stopping out areas which are to print lighter with an acid resisting varnish. A light outline can be etched in first and additional lines can be added later. The technique was invented in the 1760s by Jean Baptist le Prince (1734-81) and was introduced into England in 1774 by Paul Sandby.

The Double Elephant Print Workshop teaches printmaking using a variety of techniques and has examples of the equipment used for woodcut, intaglio and lithographic printing. During Heritage Open Days 2022 it is holding a Printmaking Heritage Day.

7. Lithography.

The process is based on the antipathy of grease and water. A flat block of limestone is used and the artist draws the design onto the polished surface either direct or by transfer, using a specially prepared greasy chalk pencil, or by laying on greasy ink with a brush. Water with nitric acid and gum arabic is rolled over the stone to fix the design by filling up the pores of stone and stopping the greasy areas from spreading. The surface is cleaned with a wet sponge and the crayon removed by washing with turpentine. Thus, when inked with a roller, only the greasy areas will accept the ink and the damp areas will repel it. The stones are printed in a special press where a squegee type pressure is applied from a travelling scraper. The process was invented in Germany 1798 by Alois Senefelder.

Lithography was used especially for music, maps, and illustrations and it was also instrumental in spreading printing to the Islamic world, which had frowned on sacred works such as the Quran being set in movable type.

Some early examples of Devon lithographic illustrations:

Rudolf Ackermann. The lime kiln and Chit Rock, Sidmouth (1819). Westcountry Studies Library.

Ackermann, Rudolf and Co. Sketches from nature of Sidmouth and its environs / after E. I. J. Sidmouth : James Wallis, 1819-1820. Somers Cocks S.55. Issued in two parts, 100 sets only. The earliest lithographs of Devon scenes but published in London. (Westcountry Studies Library: Portfolio 21 Lacks no. 10, no. 12 from different set).

Thomas Hewitt Williams. Chagford, from Holy Street (1827). Westcountry Studies Library.

From: Devonshire scenery or directions for visiting the most picturesque spots ... Exeter : Pollard, 1827. (WSL: sDEV/1827/DEV). This, the second edition of Devonshire scenery has the statement: In consequence of the new lithographic establishment of Mr. Bayley, in Exeter, six drawings have been added. He appears to have been the first lithographer to be active in Exeter.

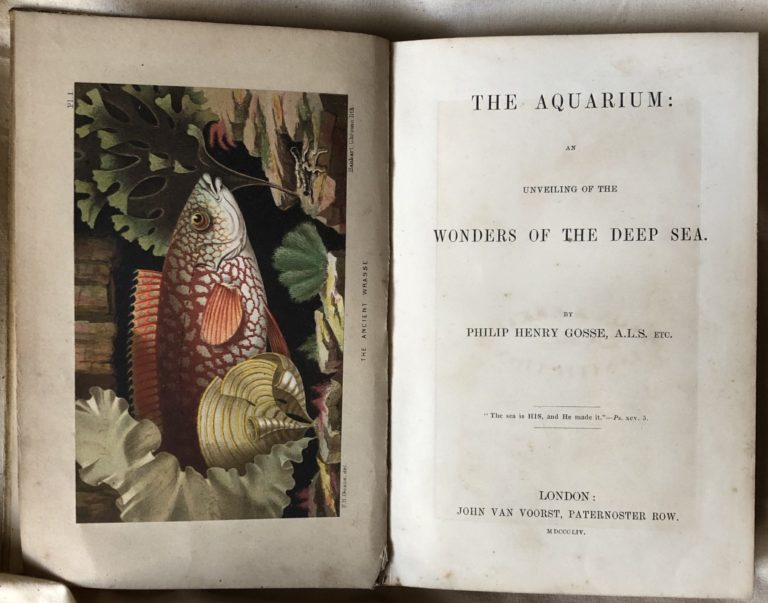

London: John van Voorst, 1854. Devon and Exeter Institution.

The Devon and Exeter Institution has a rich collection of early printed books, many of them illustrated with plates using a variety of printing techniques. During Heritage Open Days 2022 it is offering guided tours and other activities including a display on the Great Exhibition of 1851 which included many inventions in the field of printing.

8. Photography.

In 1822 the first photograph was taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, his oldest surviving photograph dating from 1826. He used a camera obscura to capture images that were exposed onto bitumen-coated pewter plates. Exposures often took hours due to the limited light-sensitivity of available materials. In 1829, Louis Daguerre, partnered with Niépce to improve the photography process. After Niepce’s death, Daguerre's experiments evolved into what is now known as the daguerreotype, shown publicly for the first time in 1839, the same year that the paper-based calotype negative and salt print processes invented by William Henry Fox Talbot was demonstrated. In 1851, the English sculptor Frederick Scott Archer invented the collodion process. With the advent of the collodion process in 1851, wet-plate photography took over as exposure times were drastically reduced, and darkrooms for development became relatively portable.

The first photographic studio in Exeter was operated by William Gill from 1842 to 1857 in a rooftop studio above what is now the Locomotive Inn in New North Road. He obtained a licence from Richard Beard, who in 1841 had bought the rights to be sole patentee of the daguerreotype process in England. Many early photographers had previously been engravers or lithographers. This was the case in Exeter with.Owen Angel (1821-1909) who set up as an engraver in about 1842, adding lithography to his skills by 1846 and photography by 1855. The largest collection of Exeter photographs in private hands is the Isca Historical Photographic Collection, at risk since the death of its founder Peter Thomas in 2020 but there are also large collections in the Devon and Exeter Institution and the Devon Heritage Centre, which recently received the photographic archive of the Express and Echo newspaper.

Francis Bedford. Exeter, Guildhall and High Street (1863?). Westcountry Studies Library.

Photographs begin to appear in local books in about 1860, one of the earliest photographers represented being Francis Bedford (1816-1894) whose Photographic views of Exeter was published in Chester : by Catherall & Prichard in about 1863 (DRO: G2/11/15/2 also copy in WSL: sB/EXE/1860/BED).

9. The moving image.

There were experiments with capturing the moving image long before the Liumiere brothers appeared in the scene in 1895. The principles of the camera obscura were known to the ancient Greeks and also in China and by Arab scholars in medieval times.It was described by Leonardo da Vinci but the name was only coined by Johannes Kepler in 1604. In 1645 the first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae included a description of his invention, the "Steganographic Mirror", a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight. The magic lantern was introduced in the 1650s, its development linked to the eminent Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens. Lantern slides were projected onto a screen and by the early 18th century extra movable layers were added to give the effect of moving pictures. Athanasius Kircher added a description of the magic lantern to a later edition of his book.

Athanasius Kircher. Ars magna lucis et umbrae, in decem libros digesta. Editio altera priori multò auctior. Amstelodami : Apud J. Janssonium à Waesberge, & haeredes E. Weyerstraet, 1671. Bill Douglas Cinema Museum.

The effect of a moving image was achieved by viewing a series of images on a rotating wheel or a looped strip in the phenakistiscope, independently invented late in 1832 by Joseph Plateau and Simon Stampfer. An improved version, the zoetrope, where the images were viewed through slits on the surface of a cylinder, was invented by William Ensign Lincoln in 1865 and with various improvements remained a popular Victoria optical toy. Chronophotogaphy, developed by Eadweard Muybridge in 1878 served a more serious purpose, the study of animal movement. Viewed through his zoopraxiscope, his series of photographs gave the impression of movement and his study of the Horse and rider has been described as the first true moving picture.

In 1891 Thomas Edison and William Dickson invented the Kinetoscope, in which a strip of film was passed rapidly between a lens and an electric light bulb while the viewer peered through a peephole. This enjoyed some popularity but did not allow for public performances. It was the Lumière brothers, Auguste Marie Louis Nicolas and Louis Jean,who achieved this on 22 March 1895 when a "cinematograph" film was projected for around 200 members of the Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale in Paris. At around the same time the Eidoloscope was created by Eugene Augustin Lauste and Woodville Latham through the Lambda Company, in New York and demonstrated for members of the press on April 21, 1895, and opened to the paying public on Broadway on May 20, but the company soon folded and the invention did not enjoy the financial success of the Lumière brothers.

All these early experiments are covered by the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum which during Heritage Open Days 2022 is offering a guided tour.

10. Digitisation.

The digital revolution has taken as long as the printing revolution to become fully established. Both revolutions lasted some three score years and ten, but almost exactly half a millennium apart. The progress of digitisation has been complex and highly technical. What follows is an extremely simplified account.

Electronic data processing began in the 1940s with early experiments conducted at Bletchley Park by Alan Turing and the construction of Colossus, perhaps the first electronic computer. After the War during the 1950s massive mainframe computers were developed by enterprises such as IBM, but were largely limited to the manipulation of mathematical data for financial and scientific purposes.

In 1949 IBM agreed to work with Father Roberto Busa, a Jesuit scholar on a project to linguistically analyse the works of Thomas Aquinas in the Index Thomisticus. Using punched tapes, it was the first use of computers to edit and analyse textual data and thus the first digital book.

An important use of textual digitisation was to produce bibliographies and catalogues. One of the earliest of these was produced by the National Library of Medicine in America, and its evolution reflects the general development of digital databases:

- 1964 MEDLARS, a large mainframe database produced a digital version of its printed Index Medicus.

- 1971 MEDLINE was inaugurated as a dial-up database.

- 1989 MEDLINE was distributed on CD-ROMs.

- 1997 PUBMED was inaugurated as a freely accessible medical database on the internet.

Libraries were anxious to benefit from computer technology and their work began in the 1960s, the era of punched cards and paper tape. In Exeter the University Library took the initiative in forming the South Western Academic Libraries Cooperative Automation Project (SWALCAP) in 1969. It developed a stock circulation system in 1976 and a cataloging system in 1978, but at first the public could only access the digital catalogue through microfiche printouts. On-line public access catalogues (OPACs) within the university were only possible in the 1980s, and an internet catalogue had to wait until the 1990s. There was similar progress in Devon's public libraries. Microfiche printouts were used together with the card catalogue from the 1970s to the 1990s when an OPAC became available. Today all major libraries, archives and museums in Exeter have their catalogues available on the internet:

Bill Douglas Cinema Museum in the Old University LibraryDevon Archives in the Devon Heritage Centre, SowtonDevon Libraries includes Exeter LibraryUniversity of Exeter includes Devon and Exeter InstitutionWestcountry Studies Library in the Devon Heritage Centre, Sowton

These online catalogues vary greatly in the type of searches they offer, the information they display and the completeness of their coverage. Some attempt to remedy this for documents linked to Devon has been made by the Devon bibliography, but this currently has limited search capability for its 100,000 records.

Parallel with the digitisation of bibliographies and catalogues, the capture of whole texts and images was initiated. One of the earliest was Project Gutenberg established in 1971, with the first books being keyboarded so that they could be available in plain text format. Optical character recognition later assisted this project and later initiatives such as the Internet Archive and Google Books which together have digitised tens of millions of titles in a variety of formats, including images of the original pages.

There have been a number of digitisation initiatives in Devon. Some examples:

- The Exeter Book Exeter Cathedral Library and Archives & University of Exeter Digital Humanities Lab

- Exon: the Domesday survey of SW England The project has been funded by the AHRC (2014–17) and is a collaboration between scholars from King's College London, the University of Oxford, and the Friends and Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral.

- Etched on Devon's memory Westcountry Studies Library funded by Heritage Lottery Fund, ran from 2002-2003 and digitised over 3,500 topographical prints of Devon, dating from 1660-1870. The functionality of the website is lost. The archived website has lost its search facility as the database format and image file names have changed. A warning about long-term preservation of digital media.

- Our region revealed: the prints and drawings collection Devon and Exeter Institution funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, The Pilgrim Trust and from Friends of Devon's Archives. Aims to digitise 9,000 images of all kinds.

- John Norden's survey of Devon manors a transcript and index of the original document of about 1613 held by the London Metropolitan Archives, currently being undertaken by volunteers with the support of Friends of Devon's Archives.

This page last updated 24 August 2022